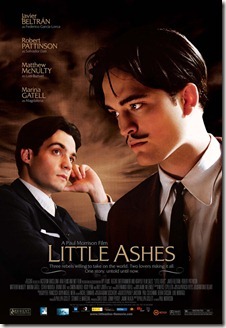

I recently watched the movie Little Ashes, a 2009 Spanish-British drama film, set against the backdrop of Spain during the 20s and 30s, as three of the era's most creative young talents meet at university and set off on a course to change their world. Luis Buñuel watches helplessly as the friendship between Salvador Dalí and the poet Federico García Lorca develops into a love affair. Years ago, I had read a book about García Lorca and had found him to be fascinating, so I wanted to see this movie. (I’ve always found Dalí to be a little strange, I had to watch the film Buñuel co-wrote and directed with Dalí, Un chien andalou (1929), or An Andalusian Dog. No matter how much I try I cannot forget the scene in which Simone Mareuil's eye is seemingly split open with a razor blade. It still freaks me out to think of it.)

I recently watched the movie Little Ashes, a 2009 Spanish-British drama film, set against the backdrop of Spain during the 20s and 30s, as three of the era's most creative young talents meet at university and set off on a course to change their world. Luis Buñuel watches helplessly as the friendship between Salvador Dalí and the poet Federico García Lorca develops into a love affair. Years ago, I had read a book about García Lorca and had found him to be fascinating, so I wanted to see this movie. (I’ve always found Dalí to be a little strange, I had to watch the film Buñuel co-wrote and directed with Dalí, Un chien andalou (1929), or An Andalusian Dog. No matter how much I try I cannot forget the scene in which Simone Mareuil's eye is seemingly split open with a razor blade. It still freaks me out to think of it.) García Lorca’s death had been mentioned and discussed in the novel Wild Man by Patricia Nell Warren. It always saddened me that this genius had been murdered by Franco’s death squad because of his political views and possible homosexuality. Therefore, after seeing the movie Little Ashes, I wanted to do a post about his poetry. Whether his poetry is about repressed homosexuality or not, is really not for me to say. I am not an expert on his poetry. I merely find it beautiful and wanted to present it with my interpretation.

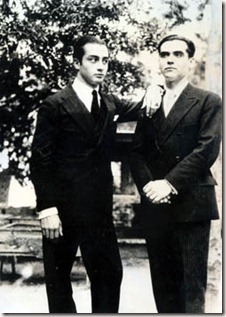

As for García Lorca’s homosexuality or bisexuality, I don’t think there is much of a historical debate about it. While it is widely acknowledged that Lorca was infatuated with Dalí, for years the artist denied entering into a relationship with Lorca. Dalí stated:

As for García Lorca’s homosexuality or bisexuality, I don’t think there is much of a historical debate about it. While it is widely acknowledged that Lorca was infatuated with Dalí, for years the artist denied entering into a relationship with Lorca. Dalí stated: He was homosexual, as everyone knows, and madly in love with me. He tried to screw me twice .... I was extremely annoyed, because I wasn’t homosexual, and I wasn’t interested in giving in. Besides, it hurts. So nothing came of it. But I felt awfully flattered vis-à-vis the prestige. Deep down I felt that he was a great poet and that I owe him a tiny bit of the Divine Dalí's asshole. He eventually bagged a young girl, and she replaced me in the sacrifice. Failing to get me to put my ass at his disposal, he swore that the girl’s sacrifice was matched by his own: it was the first time he had ever slept with a woman.Writer Philippa Goslett supposes:

It's clear something happened, no question… When you look at the letters it's clear something more was going on there... It began as a friendship, became more intimate and moved to a physical level but Dalí found it difficult and couldn't carry on. He said they tried to have sex but it hurt, so they couldn't consummate the relationship.Federico García Lorca Biography from Poets.org

Selected Sources:Federico García Lorca is possibly the most important Spanish poet and dramatist of the twentieth century. García Lorca was born June 5, 1898, in Fuente Vaqueros, a small town a few miles from Granada. His father owned a farm in the fertile vega surrounding Granada and a comfortable mansion in the heart of the city. His mother, whom Lorca idolized, was a gifted pianist. After graduating from secondary school García Lorca attended Sacred Heart University where he took up law along with regular coursework. His first book, Impresiones y Viajes (1919) was inspired by a trip to Castile with his art class in 1917.

In 1919, García Lorca traveled to Madrid, where he remained for the next fifteen years. Giving up university, he devoted himself entirely to his art. He organized theatrical performances, read his poems in public, and collected old folksongs. During this period García Lorca wrote El Maleficio de la mariposa (1920), a play which caused a great scandal when it was produced. He also wrote Libro de poemas (1921), a compilation of poems based on Spanish folklore. Much of García Lorca's work was infused with popular themes such as Flamenco and Gypsy culture. In 1922, García Lorca organized the first "Cante Jondo" festival in which Spain's most famous "deep song" singers and guitarists participated. The deep song form permeated his poems of the early 1920s. During this period, García Lorca became part of a group of artists known as Generación del 27, which included Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel, who exposed the young poet to surrealism. In 1928, his book of verse, Romancero Gitano ("The Gypsy Ballads"), brought García Lorca far-reaching fame; it was reprinted seven times during his lifetime.

In 1929, García Lorca came to New York. The poet's favorite neighborhood was Harlem; he loved African-American spirituals, which reminded him of Spain's "deep songs." In 1930, García Lorca returned to Spain after the proclamation of the Spanish republic and participated in the Second Ordinary Congress of the Federal Union of Hispanic Students in November of 1931. The congress decided to build a "Barraca" in central Madrid in which to produce important plays for the public. "La Barraca," the traveling theater company that resulted, toured many Spanish towns, villages, and cities performing Spanish classics on public squares. Some of García Lorca's own plays, including his three great tragedies Bodas de sangre (1933), Yerma (1934), and La Casa de Bernarda Alba (1936), were also produced by the company.

In 1936, García Lorca was staying at Callejones de García, his country home, at the outbreak of the Civil War. He was arrested by Franquist soldiers, and on the 17th or 18th of August, after a few days in jail, soldiers took García Lorca to "visit" his brother-in-law, Manuel Fernandez Montesinos, the Socialist ex-mayor of Granada whom the soldiers had murdered and dragged through the streets. When they arrived at the cemetery, the soldiers forced García Lorca from the car. They struck him with the butts of their rifles and riddled his body with bullets. His books were burned in Granada's Plaza del Carmen and were soon banned from Franco's Spain. To this day, no one knows where the body of Federico García Lorca rests.

- Smith, David (October 28, 2007). "Were Spain's two artistic legends secret gay lovers?". The Guardian (London). Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- Bosquet, Alain, Conversations with Dalí, 1969. p. 19–20. (PDF format)

- "Federico García Lorca." Poets.org - Poetry, Poems, Bios & More. Web. 22 Apr. 2011.

No comments:

Post a Comment